|

beauty,

health &

hygiene

general

healthcare

skincare

cosmetics

& perfumes

body

hair

cleanliness

& hygiene tools

bathing

hair

care

hair

styles

oral

care

& dentistry

intimate

feminine

hygiene

|

Medieval

Women's Body Hair

Body

hair of any kind on women is a state which appears to have been

shunned during the medieval period. This is widely reflected in

artwork of the time. Body

hair of any kind on women is a state which appears to have been

shunned during the medieval period. This is widely reflected in

artwork of the time.

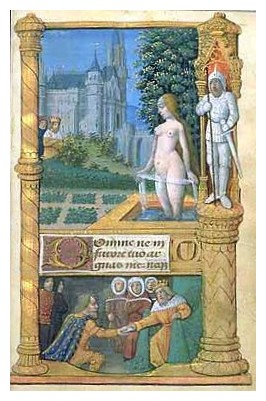

Pictured at right is a detail

from the illuminated Book Of Hours For Bourges Use dated

1500 and made in France. Although the time period is towards the

end of the medieval and start of the renaissance periods, the

woman still upholds the traits deemed desirable and beautiful-

pale, white skin, small upright breasts, generous hips, high forehead

and blonde hair.

Even though plucking the

eyebrows and hairline at the top of the forehead was commonplace

for many women, the church was extremely unhappy about this. In

Confessionale, clergymen are encouraged to ask those who

came to confession:

If she has plucked

hair from her neck, or brows or beard for lavisciousness or

to please men... This is a mortal sin unless she does so to

remedy severe disfigurement or so as not to be looked down

on by her husband.

Many

books cite small tweezers made from copper alloy or silver as

part of medieval toiletry sets. The tweezers at left are dated

from the 15th century and feature brass tweezers, an earscoop

and a nail pick, all hinged to fold away when not in use. Many

books cite small tweezers made from copper alloy or silver as

part of medieval toiletry sets. The tweezers at left are dated

from the 15th century and feature brass tweezers, an earscoop

and a nail pick, all hinged to fold away when not in use.

Contemporary

artworks, when they show the female private parts at all, show

it clear from any growth of hair. Since the general practice of

tweezing the face and hairline to achieve a fashionable look was

popular, it is not hard to imagine that women may have also removed

the unwanted hair from the pubic region. The image at right, shows

a rare image where the female genitals are shown completely uncovered,

giving us a view of her private parts, which are hairless. Contemporary

artworks, when they show the female private parts at all, show

it clear from any growth of hair. Since the general practice of

tweezing the face and hairline to achieve a fashionable look was

popular, it is not hard to imagine that women may have also removed

the unwanted hair from the pubic region. The image at right, shows

a rare image where the female genitals are shown completely uncovered,

giving us a view of her private parts, which are hairless.

Trotula de Ruggiero's 11th

century treatice, De Ornatu Mulierum (About Women’s

Cosmetics) advises a hair removal remedy for women:

In order permanently

to remove hair. Take ants' eggs, red orpiment, and gum of

ivy, mix with vinegar, and rub the areas.

A written reference to female

pubic hair is in the telling of the tale of Griselda, a

popular story many times retold, of a cruel husband and his submissive

and enduring wife. In one version, the husband Gualtieri discusses

the type of woman who when turned out of her house in only a chemise

would warm her wool or rub her pelt against another

man to procure fine clothing. It is fairly certain the the wool

and pelt referred to is the woman's pubic hair. From this we can

ascertain that at least some women retained their hair.

Chaucer, too, in the Miller's Tale talks a woman who is bearded

around hir hole.

To counter this view, Erasmus

in his work The Praise of Folly speaks of an old woman

buying herself a younger lover saying:

Nowadays any old dotard

with one foot in the grave can marry a juicy young girl, even

if she has no dowry.. But best of all is to see the old women,

almost dead and looking like skeletons who have crapt out

of their graves, still mumbling "Life is sweet!"

As old as they are, they are still in heat still seducing

some young Phaon they have hired for large sums of money.

Every day they plaster themselves with makeup and tweeze their

pubic hairs; they expose their sagging breasts and try to

arouse desire with their thin voices.

Even though this text was

written in 1509, it shows that at that point, it was normal for

a woman to be without pubic hair. Whether this extended to the

peasantry is doubtful and whether it extended to all of the European

countries can only be guessed at.

Copyright

© Rosalie Gilbert

All text & photographs within this site are the property of

Rosalie Gilbert unless stated.

Art & artifact images remain the property of the owner.

Images and text may not be copied and used without permission.

|