The

Chemise, Shift or Smock

STYLES - FABRICS - DECORATION

The

chemise, shift or smock was the innermost layer of the medieval

lady's dresses, much like a petticoat or slip of our grandmother's

day. It was worn next to the skin to absorb bodily odors and keep

the outer layers smelling fresher for longer. Great robes, houppelandes

and kirtles could be heavily embellished with embroidery and semiprecious

stones, so it was wise to keep the laundering of the outer robes

to a minimum. The

chemise, shift or smock was the innermost layer of the medieval

lady's dresses, much like a petticoat or slip of our grandmother's

day. It was worn next to the skin to absorb bodily odors and keep

the outer layers smelling fresher for longer. Great robes, houppelandes

and kirtles could be heavily embellished with embroidery and semiprecious

stones, so it was wise to keep the laundering of the outer robes

to a minimum.

In 1313, Anicia atte Hegge,

a widow from Hampshire, made a will on the surrendering of her

holding to her son which included the stipulation that she would

be provided with various items of clothing including:

...a chemise worth

8d each year.

Styles

of chemise

There

appear to be three distinctly different styles of chemise or smock.

Contemporary illustrations usually show men and women naked in

the bedchamber, but occasionally show women modestly in their

underclothes. From these images, and from existing garments we

can deduce what was worn under the outer clothing. There

appear to be three distinctly different styles of chemise or smock.

Contemporary illustrations usually show men and women naked in

the bedchamber, but occasionally show women modestly in their

underclothes. From these images, and from existing garments we

can deduce what was worn under the outer clothing.

The first style seems to

be made of an opaque fabric, probably linen, constructed with

fitted sleeves and not overly shaped through the body. It can

be seen at right in the detail from the early 1400's illumination

Dionysus I humiliates the women of Locri. The woman are

in the process of removing their outer clothing and the chemise

shown appears to be a reasonable thickness, almost certainly thick

linen.

The

second type of chemise appears to be a strapless or shoestring

strap type of petticoat-like dress which could vary in length

from knee to shin length. The detail at left is taken from the

Wenceslas Bible, dated around 1390-1400. It shows two women

in their underclothes tending to a man in a bath. The

second type of chemise appears to be a strapless or shoestring

strap type of petticoat-like dress which could vary in length

from knee to shin length. The detail at left is taken from the

Wenceslas Bible, dated around 1390-1400. It shows two women

in their underclothes tending to a man in a bath.

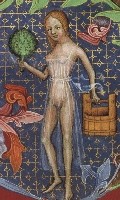

There

are also quite a few bathing images from 14th century Bohemian

manuscripts where women are shown with wooden buckets and are

wearing chemises. Some of these are semi-opaque but others, like

the detail shown at right, are quite sheer. Almost all of these

are of a similar style- a garment with thin shoulder straps and

no sleeves. There

are also quite a few bathing images from 14th century Bohemian

manuscripts where women are shown with wooden buckets and are

wearing chemises. Some of these are semi-opaque but others, like

the detail shown at right, are quite sheer. Almost all of these

are of a similar style- a garment with thin shoulder straps and

no sleeves.

The third style of chemise

seems to have persisted from through to the renaissance where

it was clearly visible through slashed clothing and at necklines.

It is a more voluminous style, has puffed sleeves and appears

to be made of a finer type of fabric than the opaque linens previously

worn by women.

Fabrics

It would appear that the overwhelmingly most common fabric used

for the chemise or smock are linens of varying qualities according

to the social position of the wearer and the finances available.

We know that according to current health beliefs, wool worn next

to the skin was thought to be bad for the humours, and should

be tempered with a layer of linen underclothing. In art, we see

that chemises and smocks,  along

with men's under shertes and breeches, are almost always white. along

with men's under shertes and breeches, are almost always white.

According to Francoise Piponnier

and Perrine Mane in their book, Dress In The Middle Ages,

peasants and the less affluent would have worn hemp underclothes

which were less expensive than linen. The

detail at left from the 1330-40 painting Scenes From The Life

Of St John The Baptist appears to show a fabric of reasonable

weight and stiffness suggesting linen.

In several instances we hear

of noblewomen who become nuns and renounced their silken underthings.

According to one written reference, a noble lady took up a hair

shirt to replace her underclothes of silk as part of her penitence.

This suggests that ladies of high society may have enjoyed luxurious

silken chemises.

Decoration

Generally, the chemise during the medieval period is depicted

as plain and white. Later in the Renaissance, many had blackwork

embroidered at the neckline and sleeves. It does appear, however,

that the chemise during the medieval period may have been decorated

at least sometimes.

In

the 13th century, we read a poem by an unknown author who laments

the Sumptuary Laws and the restrictions on her clothing and in

particular, her chemise. She says that she can no longer wear

her white chemise which is richly embroidered with silk in bright

colours and gold and silver. She bemoans: In

the 13th century, we read a poem by an unknown author who laments

the Sumptuary Laws and the restrictions on her clothing and in

particular, her chemise. She says that she can no longer wear

her white chemise which is richly embroidered with silk in bright

colours and gold and silver. She bemoans:

Alas, I dare not wear

it!

indicating not only that

in her time period at least, the chemise could be richly embroidered

with silk and precious metal thread and also that the Sumptuary

Laws which were often largely ignored, were partially effective

at times. It also indicates that her chemise may have been seen

and was not entirely concealed by her outer clothing.

In 1298 the Consol of Narbonne

passed a law against laced outer dresses which allowed the pleated

and embroidered under-chemise to show. This tells us that at that

period also, at least, the chemise could also be pleated and embroidered.

For a law to need to have been passed, it stands to reason that

it must be an occurrence common enough for it to be a concern.

Later into the 14th century,

all images in art show a tunic style unpleated garment. Heading

into late 14th century, Italian art starts to show the pleated

chemise which was designed to be seen down the arms. Shown at

right above, is a detail from 1484 Master Of The Housebook's The

Uncourtly Lovers which shows a chemise decorated with gold

and pearls. By the late 15th century, it was extremely common

to see the chemise, which might be finely pleated and have needlework

at the top which could be seen.

Copyright

© Rosalie Gilbert

All text & photographs within this site are the property of

Rosalie Gilbert unless stated.

Art & artifact images remain the property of the owner.

Images and text may not be copied and used without permission.

|