|

Medieval

Deaths, Funeral Rites & Rituals

MEMORIAL BRASSES - VIGILS & MASSES - THE BLACK

DEATH - BURIAL PROCEDURES - WIDOWS

The

afterlife and the soul of the deceased was a very serious business

to those who lived and died in the Middle Ages and great consideration

was given into preparation for the soul's eternal life. The final

preparation of the body for burial was seen as just as important

as the life of the person who lived it. The

afterlife and the soul of the deceased was a very serious business

to those who lived and died in the Middle Ages and great consideration

was given into preparation for the soul's eternal life. The final

preparation of the body for burial was seen as just as important

as the life of the person who lived it.

The detail shown at right is the Dance of Death by Talin,

of the mortality of man and the inability of even the upper classes

and kings to escape Death's clutches. The Dance of Death was a

popular theme in contemporary medieval artwork.

While death came to all,

its repercussions varied depending on the social stature of the

deceased.

When an unfree tenant passed away, a heriot or fine was

paid to his Lord; usually his best beast. It was written in the

Cuxham Court Roll that

'...even if he has only

a single animal, the Lord shall have it.'

The parish church claimed

the second-best beast as a mortuary fine. If a family was of modest

standing, it was quite possible to lose all the beasts it possessed,

especially if illness claimed more than one family member within

a short space of time.

Memorial

Brasses

Memorial brasses were a popular way for the wealthy to be remembered

after death, originating perhaps from the desire for memorials

more durable than the usual stone and marble slabs.  Brass

plates also offered the ability to record greater detail in clothing

and accessories than stone or marble. Brass

plates also offered the ability to record greater detail in clothing

and accessories than stone or marble.

The earliest existing dated examples of memorial brasses are from

the thirteenth century. The brass, an alloy of copper, zinc, lead

and tin was beaten into thick plates of various sizes and was

principally manufactured at Cologne and exported. England was

the largest consumer of brass for use in brass memorials.

Pictured at left, a memorial

brass of Elizabeth de Northwood dated at 1335. She is engraved

modestly wearing a wimple over her plaited hair which is resting

on an elaborate pillow.

Persons commemorated with brasses were usually engraved on the

plates life sized by deeply incised lines. Shading and minute

detail was not usually attempted. In some cases black and red

enamels were used to enhance the brass, while others brasses were

further adorned with Limoges enamels which could be many varied

colours.

Brasses were at their greatest artistic excellency in the 14th

century, slowly deteriorating in the following centuries. The

most popular pose for women was the hands pressed palms together

in devotional prayer. Often a couple were shown together and sometimes

a beloved pet was included at the feet.

Vigils

and Masses

Much expense was spent by the upper classes on candles, masses

and donations to the church. Funerals were not only to mark the

passing of a loved one, but for the nobility or very wealthy townsfolk,

it was another opportunity for a showy display of wealth.

An elaborate funeral pall was often donated to the church to be

made into vestments or altar cloths afterwards and great sums

of money or lands donated to the church ensured prayers were said

for the soul of the departed.

Common people sat vigil with

the deceased, often singing, playing games and dicing. In an effort

to curtail these kinds of vigils which, in 1284, were felt by

the Ludlow church to be not particularly solemn, the guilds forbade

games and the attendance of women who were not direct family members.

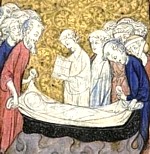

Shown at right is a detail from the Murthly Hours, a 1310

illumination.

Guilds provided for their

own members even at the time of death with donations of masses,

tapers and burial costs, extending this to members of the guild

who lived outside of the town. It was standard practice that the

deceased would be afforded the same courtesies as if he had died

in his home parish.

The

Black Death The

Black Death

The bubonic plague, known then as the Great Pestillance and now

as the Black Death, swept through Europe decimating populations

from 1347 to 1350 and again in 1399. It was widely believed by

rich and poor alike to be a punishment from God for the wickedness

of the people who lived indulgent lives at that time.

In actual fact, it is thought today that the plague was carried

by flea-infested rats. To the unlearned and educated alike, the

plague struck entire families down, randomly sparing a person

here and there. An estimated 25 million Europeans died.

Appointments to the church

were hastened to fill the urgent need for spiritual ministering

as the church also suffered losses among its numbers. As the numbers

of deaths grew and grew, mass graves were dug outside town walls

and last rites were not performed since there was no-one left

alive or willing to administer them.

Burial

Procedures

The body of the deceased was washed with water and then wound

in a white winding sheet or shroud in preparation for burial.

Illustrated above is a scene from the illumination The Murthly

Hours of 1310 showing a scene from a burial with the deceased

already wrapped in his winding sheet and being lowered into what

appears to be a casket of some kind while prayers are being read

from a book. Both women and men are in attendance.

The

illumination at right shows another image from the same page of

The Murthly Hours manuscript of the funeral procession.

The procession is led by a person with a bell followed by monks,

then men, the deceased and finally by women. The funeral pall

is covering the deceased. The

illumination at right shows another image from the same page of

The Murthly Hours manuscript of the funeral procession.

The procession is led by a person with a bell followed by monks,

then men, the deceased and finally by women. The funeral pall

is covering the deceased.

Funeral palls were often

made of very costly material which was donated to the church afterwards

in return for masses for the departed's soul.

Rosemary, Rosmarinus officinalis, symbolic of memory and

fidelity, was used in wreaths for funerals.

Widows

The life of a widow often offered more opportunities than the

life of a married woman. In many cases, she was permitted to continue

her husband's business if she was previously trained in the trade.

She was then permitted to employ up to two apprentices and oversee

their training herself and confer guild status on her next husband

provided he worked at the same craft.

Listed in the records of The Company of Soapmakers of Bristol

are entries such as:

'The Wiiddowe Dies took

to prentice Michaell Pope the Son Richarde Pope of Bristeltowe

for the terme of VII yeares begininge the III of October 1593'

and also among the records...

'We reserved into the

fellowship of Sopmaken and changleng Richard Lemwell for that

he sarved his Apprentisshipe with Alice Lemwell wedow to sopemaken

and changlyng'

Register

of Rich Widows

A widow who was wealthy and of sufficient social standing naturally

attracted the attention of noblemen hoping to utilise her assets

to improve his own position. Widows of sufficient means or with

a large inheritance or with strategic land holdings might be put

under the king's 'protection'. The Register of Rich Widows

and Orphaned Heirs and Heiresses of 1185 shows that many were

married 'in the king's gift'.

Essentially, the king was within his right to grant the widow

in marriage to whomsoever he pleased.

It was possible for a widow to avert a match she wished to avoid

by buying her way out of such an agreement, however it was not

uncommon that the price to do so was extremely high and would

cost the widow the means to support herself afterwards, thus making

it impossible for a woman to free herself.

In many cases, it left her with little choice but to comply, unless

she took the mantle and the ring and became a vowess dedicating

her life to the service of God and promising to remain chaste.

Copyright

© Rosalie Gilbert

All text & photographs within this site are the property of

Rosalie Gilbert unless stated.

Art & artifact images remain the property of the owner.

Images and text may not be copied and used without permission.

|