General

Medieval Healthcare

HEADACHES - WEIGHT LOSS - WORMS - WARTS &

CORNS - MOSQUITO REPELLENTS

BODY ODOUR - ANTISEPTICS - TOILET PAPER

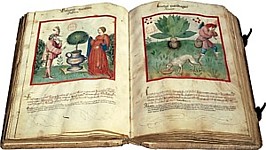

Perhaps the best-known medieval

medical journal is the late 14th century Tacuinum Sanitatis,

shown above, which was a medical codex with almost full-page,

colour illuminations. There are several existing copies of this

book which vary slightly, but contain, for the most part, the

same information.

One copy was written and illuminated for the Cerruti Family and

was probably made from Verona. The Tacuinum Sanitatis dealt

with many aspects of healthcare- herbs, substances, emotions and

types of fabrics. It tell of the benefits and dangers of each

and what to do about them.  Much

of what we know today about medieval healthcare comes from these

manuscripts. Much

of what we know today about medieval healthcare comes from these

manuscripts.

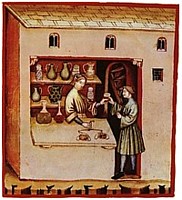

The detail at left, is from

the Tacuinum Sanitatis and shows a man purchasing medicine

from an apocathary. The scales on the bench were used to give

correct measure for many of the complicated recipes used.

Only a few textbooks survive

specifically dealing with women's health, although it must be

supposed that medieval women faced the same kind of daily complaints

as the modern woman.

Headaches, ringworm and warts were seen as curses from a displeased

God, but home remedies went hand in hand with prayers for the

cure of many ailments.

Icons Icons

Religious items were genuinely believed to aide with many aspects

of healthcare- whether relief for a mother in labour or for assistance

with plague. Looking at an image of Saint Christopher was devoutly

believed to give protection from sudden death for the next 24

hours.

Wearing a ring or brooch with the names of the three wise men-

Caspar (or Jaspar), Melchior and Balthazar-

was also good to epilepsy preventative.

Reliquaries, which held a small piece of religious artifact, were

a guaranteed recipe for good health and protection from sickness.

The Lamb of God reliquary from the Gilbert Collection,

seen at right, would have held a small piece of holy artifact

or a small item blessed with holy water.

Many 13th and 14th century rings were also inscribed with the

letters A.G.L.A. which were to aid against fevers.

Treatices

& books

Hildegard von Bingham, a twelfth century German woman physician,

wrote on women's health, as did Gilbert the Englishman in the

13th century. His compilation of remedies are based on a Latin

medical textbook and is known as The Sickness of Women.

The Tacunimum Sanitatus had an extensive list of natural herbs,

foods and plants and what they were good for.

Bloodletting

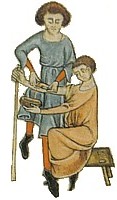

was believed to release vile humours from the body through the

wound and was widely practiced on both men and women. The picture

at left is a detail form the 14th century illumination, the Luttrell

Psalter and shows a doctor releasing blood from an ailing

patient. Bloodletting

was believed to release vile humours from the body through the

wound and was widely practiced on both men and women. The picture

at left is a detail form the 14th century illumination, the Luttrell

Psalter and shows a doctor releasing blood from an ailing

patient.

Many herbal remedies were

utilised throughout the Middle Ages, some of which persist today.

Taking honey for a sore throat in these modern times certainly

does not raise any eyebrows and was a common remedy in the middle

ages. Listed below are home herbal preparations recorded for use

from as early as the 12th century.

Please don't try these at home. They made be injurious or inflict

harm.

DO

NOT TRY THESE AT HOME!

Headaches

It is written in Culpepper's Herbal, that vervain, Verbena

officinalis, warded off headaches, although it it not specified

how. A 15th century recipe for relief of the migraine gives more

thorough instructions;

..take half a dish of

barley, one handful each of betony, vervain and other herbs

that are good for the head, and when they be well-boiled together,

take them up and wrap them in a cloth and lay them to the sick

head and it shall be whole...

Weight

loss

It

seems that as now, the medieval woman could be concerned with

her weight. It

seems that as now, the medieval woman could be concerned with

her weight.

One did not wish to be thin, as this indicated the lack

of means to feed oneself properly, however after childbirth or

when weight became greater than desired, slimming tonics were

called for.

To enhance loss of weight, fennel, Foeniculum vulgare, at

right, seeds are reputed to make people lean that are too fat.

Garden patience or Great monk's rhubarb roots were also used in

diet drinks.

Worms Worms

Garlic, Allium sativum, at left, was eaten whole like a

vegetable. Warm and dried, it was given against poisons but also

to kill worms while onion, Allium cepa, steeped all night

in springwater kills worms if taken after morning fasting.

Another cure is made thus:

Take lime and twice as

much chalk and with wine or water, make a thin cement. Apply with

5 days with a feather to the area where the worm is. On the fifth

day, take aloe and a third as much myrrh, crush and with fresh

wax, prepare a plaster. Use hemp cloth and tie on for 12 days.

Warts

and corns tinctures

The sun dew juice unmixed and applied topically will destroy warts

and corns. Spurge or garden spurge milk is good to take away warts

if applied externally.

Mosquito

repellents

Pennyroyal, Mentha pulegium, was popular as a flea dispeller

scattered or burnt in rooms, and the leaves were rubbed on the

skin to deter insects.

Deodorant

The texts attributed to Trotula offer a remedy for body odour

for women. It says this:

There are some women

who have sweat that stinks beyond measure. For these we prepare

a cloth dipped in wine in which there have been boiled leaves

of bilberry, or the herb itself or the bilberries themselves.

Antiseptics

Marshmallow,

Althaea officinalis; Ivy, Hedera helix and Thorn

apple, Datura stramonium were still used in twentieth century

rural England to soothe injuries, burns and insect bites and have

been handed down for generations as herbal remedies. Marshmallow,

Althaea officinalis; Ivy, Hedera helix and Thorn

apple, Datura stramonium were still used in twentieth century

rural England to soothe injuries, burns and insect bites and have

been handed down for generations as herbal remedies.

Alum and pomegranate, Punica granata, at right, are mentioned

by Roger of Frugard as ingredients in a lotion to overcome suppuration,

and are astringents.

Banckes' Herbal written

in 1525 suggests Rosemary, Rosmarinus officinalis as a

medieval antiseptic writing:

boil the leaves in white

wine and wash thy face therewith, thy beard and thy brows, and

there shall no corns grow out, but thou shall have a fair face.

Toilet

paper Toilet

paper

Although toilet paper- squares made from rice paper which was

cheap and plentiful- was known in China as early as the 6th century,

it was noted with horror that the Chinese only wiped and not washed

with water as other Europeans did.

It seems that toilet paper,

and indeed the idea of toilet paper, was unappealing to

early Europeans and the use of paper squares was not adopted back

home.

Obviously, some kind of wiping

system or device was used during the middle ages. There appear

to be two that we know of today- gomphus or the gomph

stick and torchcut or torche-cul.

The gomph stick was a curved

stick and used as we use toilet paper- to scrape.

The torche-cul refers to

straw which was used in the toilet. It literally translates as

'arse-wipe' or 'arse-torch' indicating that the straw was used

either for lighting in the toilet or as a substance to wipe with.

Some people assert that Spaghnum moss was used to wipe

with and while we don't know for sure, we find its presence in

cess pits. The manuscript image to the right (source unknown)

shows an outdoor privvy with two seats and a supply of what might

be straw in the rack above.

Perhaps water was supplied

for washing down below as well as for the hands and face, but

if so, it is not mentioned anywhere I've seen to date.

Copyright

© Rosalie Gilbert

All text & photographs within this site are the property of

Rosalie Gilbert unless stated.

Art & artifact images remain the property of the owner.

Images and text may not be copied and used without permission.

|