|

a

woman's

life

births

weddings

divorces

death

& dying

manners

cooking

housework

shopping

gardening

livestock &

poultry care

education

employment

opportunities

recreation

& hobbies

holidays

&

feast days

board

games

music

embroidery

& needlework

pet

keeping

reading

dancing

horseriding

hawking

hunting

sex &

sexual health

PLEASE NOTE!

ADULT THEMES!

|

The

Very, Secret Sex Lives of Medieval Women

Sex, Sexual Health, Contraception and Sexuality

CHURCH PROHIBITIONS - SEXUAL HEALTH - APHRODISIACS

- PROCREATION

CONTRACEPTIVES & ABORTIVES - PROSTITUTE- THE CULT OF THE VIRGIN

- - ADULT THEMES - -

The

Very Secret Sex Lives of Medieval Women is now a book! You

can find information about it in the BOOK

tab at the top of the page. This page contains a very small overview

of some of the key elements in a medieval woman's private life. The

Very Secret Sex Lives of Medieval Women is now a book! You

can find information about it in the BOOK

tab at the top of the page. This page contains a very small overview

of some of the key elements in a medieval woman's private life.

Unlike today, a woman's status

in society wasn't gauged by her age or profession, but by her

sexual status.

She was either (ideally) a virgin, a wife or a widow. Her rights

and obligations were dependent on these. Holy women, who may have

at one time been wives or widows and may no longer have been actual

virgins, were considered virgins as brides of Christ and usually

fell into the same category as unmarried, and therefore chaste,

women. An unmarried woman who was not a virgin, either because

she was a mistress or prostitute found herself on tenuous ground

both legally and in society.

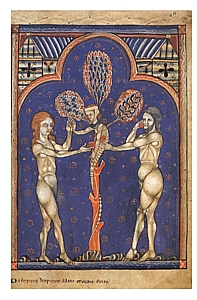

Church

prohibitions

On the subject of sex, the church had much to say.

Not only did it have differing

opinions of the goodness women in general, it also recognised

the need for men to marry and produce heirs.  Obviously,

all women were sinful descentants of Eve from the Garden of Eden,

who was not loved much by the church. This feeling was echoed

from the pulpit by men who weren't very keen on women as a gender.

The 11th century cardinal Peter Damien wrote that; Obviously,

all women were sinful descentants of Eve from the Garden of Eden,

who was not loved much by the church. This feeling was echoed

from the pulpit by men who weren't very keen on women as a gender.

The 11th century cardinal Peter Damien wrote that;

...woman is Satan's

bait.. poison for men's souls..

The church acknowledged that

a woman was required as part of God's play to go forth and multiply.

A woman shouldn't, however, enjoy sexual relations. It

was something to be endured for the sake of procreation.

Since sex couldn't be forbidden entirely, restrictions on when

relations could take place were in place. Listed below are some

of the times when it was not permissible to have sex, even with

one's own husband.

Sex was not permitted on a Wednesday, or a Friday, on a Sunday,

or Saturday, on any of the 60 church feast days, during lent,

during Advent, during Whitsun week, Easter week, while a woman

is menstruating, while a woman is pregnant, while a woman is breastfeeding,

within the walls of a church, during daylight, if she is completely

naked, for the eight days leading up her husband taking the Eucharist

or if the couple was related, even by marriage. The only permissible

position was the missionary position.

The church confessional became increasingly personal. Priests

could ask the most personal questions about a woman's most private

practices. Among the questions listed in an 11th century Confessors

Manual, are questions specifically aimed at women-

Have you made a

tool or device in the shape of a penis and tied it to your

private parts and fornicated with other women with it? Have

you swallowed semen to enhance your husbands desire?

The fact that the church

felt the need to even ask this question tells us a certain amount

about sex practices which were frowned upon, even if they didn't

involve sex with men.

Sexual

health

It was believed that sex was a requirement for a woman's ongoing

good health. A husband's impotency was taken quite seriously,

as it was believed that a woman needed regular sexual intercourse

for her emotional and physical well-being.

The

humors which would build up inside her if she was denied her could

lead to madness, convulsions, fainting fits, suffocation of the

womb and hysteria. A woman could divorce a man for his inability

to perform. The

humors which would build up inside her if she was denied her could

lead to madness, convulsions, fainting fits, suffocation of the

womb and hysteria. A woman could divorce a man for his inability

to perform.

Thomas of Chobham devised

a method to determine if a husband was was absolutely impotent.

He approved a physical examination of the man's genitals by 'wise

matrons', followed by a bedroom trial:

'after food and drink,

the man and the woman are to be placed together in one bed and

wise women are to be summoned around the bed for many nights.

And if the man's member is found to be useless and as if dead,

the couple are well to be separated.

There are documented court

cases in both 1292 at Canterbury and 1433 in York where wise women

testified against the husband in cases such as this. It was not

unusual that the wise matrons were family members or known to

the man. This could hardly improve performance issues he may have

been having.

Aphrodisiacs

Trying to encourage a potential lover or husband is a thing we

do even today. We associate certain foods and herbs with being

sexy or promoting desire. Medieval aphrodisiacs were not of the

ilk that we hope for today. Today we think champagne, caviar and

oysters. Or chocolate. The medieval woman was unlikely to find

any of these on her list of things to inflame the passions, so

what might she consider? Onions. Let's start with onions.

The Four Seasons of the House of Cerruti, which is a copy of the

Tacuinum Sanitatis from the 14th century Vienna has this

to say:

An excellent thing,

the onion, and highly suited for old people. They generate

milk in nursing mothers and fertile semen in men.

A different translation of

the same manuscript, the Tacuinum sanitatus, Paris, folio

24v, has this to add:

Onion. (Cepe)

Nature: (according to Rasis) warm in the fourth degree, moist

in the third.

Optimum: The white ones which are watery and juicy.

Usefulness: They are diuretic and fecilitate coitus.

Dangers: They cause headaches.

Neutralisation of the dangers: With vinegar and milk.

One might think that onion

breath might be somewhat off-putting, but the manuscript fails

to tell us how to prepare them for the desired effect. It also

causes a confusing conundrum. It increases the desire but at the

same time gives a headache.

Hildegarde von Bingen recommended steering away from them altogether

and wasn't a fan at all.

Garden

Nasturtiums are also recommended. If you look closely at the seeds,

you might feel that they look quite similar to a certain male

genitalia, and you'd be right. Garden

Nasturtiums are also recommended. If you look closely at the seeds,

you might feel that they look quite similar to a certain male

genitalia, and you'd be right.

Attributing properties to foods and plants in the natural world

based on things it reminded one of, was called the Doctrine

of Signatures. It was understood that since God had created

all things, both good and ill, health and disease, then he had

put the cures for all ills here on earth with us, we only needed

to find them.

We would find them, it was thought, by seeing similarities in

the physical object and what it was needed to cure.

If a bean looked like a kidney, it stood to reason that it would

be helpful medicinally for the kidney. So, in this way, nasturtium

seeds, which resembles testicles, would be helpful to augment

the sperm and coitus. Several

versions of the Tacuinum

sanitatus include

the uses: Augment the sperm and coitus but cause migraines (Vienna,

f 30v) and Augments

the sperm and coitus but also causes migraines (Casanatense,

f.LIV.)

Asparagus

should also be helpful to increase desire. The Four Seasons

of the House of Cerruti assures us it absolutely was. It tells

us: Asparagus

should also be helpful to increase desire. The Four Seasons

of the House of Cerruti assures us it absolutely was. It tells

us:

Pick those young stalks

whose tips point downwards. They open up occlusions which

prevent the humours from flowing regularly through the body's

passages, and they stimulate carnal relations. Asparagus is

harmful to the intestinal hairs unless it is first boiled

in salted water with vinegar.

The fact that it is male

member-shaped isn't worth thinking about. Another version of the

same manuscript from Vienna, tells us that it influences coitus

positively, but doesn't say for which gender.

A medieval woman who wants something a little more all-purpose

could turn to leeks. They stimulate urination, influence coitus

and, when mixed with honey, clear up catarrh of the chest, according

to that quite-reliable source of herbal healthcare, the Tacuinum

Sanitatis. Rather unhelpfully, it doesn't clarify whether

the coitus is influenced for the better or worse.

Sex

for procreation Sex

for procreation

Producing an heir was serious business for the medieval family

and a woman was expected to provide a male heir to keep the family

name, business and land holdings. A marriage was often not deemed

proper until coitus had taken place, sometimes with witnesses.

The image detail at left comes from a 13th century manuscript

the Maciejowski Bible, from France. It shows a king in

bed with a woman who has her hair sensibly arranged in a coif.

Medieval manuscripts offered advice to lift a libido or assist

if pregnancy was desired. The Tacuinim Sanitatus, from

Vienna, also known as The Four Seasons of the House of Cerruti,

offers this herbal advice:

Sage: It is good for

the stomach and cold diseases of the nerves. It's digestion

is slow but can be speeded up with honey. We read that if a

woman who has slept alone for four days drinks this and then

has sexual relations, she will immediantly become pregnant.

To this end, women who survived the plague in one town in Egypt

were made to drink the juice of sage leaves so the town could

quickly be repopulated.

There was other advice on

the best times for sex to produce male heirs and there were many

recipes to guarantee a pregnancy. Herbal books such as the Tacuinum

Sanitatus from the 14th century offered herbal remedies almost

certainly guaranteed the gender of choice, as did Trotula, who

is reknowned for her weasel testicle recipes.

Contraceptives

and abortives

Rather surprisingly, medieval women did know about and use contraception.

Since childbirth was so perilous, many women desired contraception

which was roundly condemned by the church. St Augustine declared

that any woman, whether she was married or otherwise, became a

whore in the eyes of God if she used contraceptives, as the only

reason for sexual intercourse was procreation.

Abortion was also frowned upon as it was stated in the dictum

that a fetus had a soul of its own after 40 days. In both civil

and canon law in 13th century England, abortion was condoned in

certain conditions only- in the case of an unborn child endangering

the life of the mother, it was the life of the mother who was

to be saved. Debates on contraception for a woman who had previous

complications with pregnancy were held with great seriousness.

Should a woman refrain from sex so that she might not conceive

and possibly die in childbirth? What about her martial obligations?

Were contraceptives permissible in situations such as these?

Luckily, breastfeeding and

poor nutrition provided a certain amount of contraceptive measure

for peasant woman. Women in higher society were more likely to

have wet nurses and better diets and thereby ran the risk of pregnancy

sooner than her poorer counterpart.

One contraceptive measure

recorded by medieval German women is using beeswax and rags to

form a physical block. Other popular herbal compounds used rosemary

and balsam with or without palsley (parsley?)

Trotula

offered many helpful herbal remedies, and a few rather strange

ones. Her most famous is the one with the weasels: Trotula

offered many helpful herbal remedies, and a few rather strange

ones. Her most famous is the one with the weasels:

Take a male weasel and

let its testicles be removed and let it be released alive. Let

the woman carry these testicles with her in her bosom and let

her tie them in goose skin or in another skin, and she will

not conceive

A future Pope wrote about

contraceptives for men in his book The Treasure of the Poor.

A plaster made of hemlock, pictured at right, applied to the testicles

of the husband prior to the sexual act was recommended as a male

contraceptive.

Medieval

prostitutes

Women who made their living in the sex industry were as active

in the middle ages as they are today. Prostitutes were generally

looked down upon but deemed to be a necessary evil- something

that society needed but would rather not talk about.

Shown

at right is a detail from the 1400-1409 painting Paul The Hermit

Sees A Christian Tempted. Shown

at right is a detail from the 1400-1409 painting Paul The Hermit

Sees A Christian Tempted.

At times women who were prostitutes wore visible markers on their

clothing to identify them with their trade. Ironically,

at certain periods over the Middle Ages, prostitutes were exempted

from sumptuary laws because it was acknowledged that a women in

that line of work required certain things to make her desirable

in order to make a living.

Dress in the Middle Ages by Francoise Piponnier and Perrine

Maine state that:

The striped cloak

.. in Marseilles.. the striped hood worn in England, the white

hood of Talouse, the black and white pointed hat of Strasbourg

were increasingly replaced by bands of fabric stitched to

the sleeve or the shoulder, then by tassels worn on the arm.

The church, although scathing

in their condemnation of sex and women who have it generally,

were not above being involved in the industry. A brothel in Dijon,

France, lists twenty per cent of its clients as churchmen.

It's also recorded that the Bishop of Winchester received regular

rent from the brothels of Suffolk.

Guidelines were needed to regulate the hours and wages of prostitutes

so that the women might not be taken advantage of. In that way,

the industry was regulated with fixes wages and working hours.

There were always women who worked outside these, though, and

these were the women forced into prostitution against their will

by mothers, family, ladylords or brothel owners who were disreputable.

The

Cult of the Virgin

Many

clergy despised woman as instigators of original sin and for their

general weakness although there was the issue of the Virgin Mary

who really made things tricky. Mary was a woman, and Christ's

mother, and therefore the holiest and purest of all women, and

as an example of womanhood, could not be faulted. Many

clergy despised woman as instigators of original sin and for their

general weakness although there was the issue of the Virgin Mary

who really made things tricky. Mary was a woman, and Christ's

mother, and therefore the holiest and purest of all women, and

as an example of womanhood, could not be faulted.

Many female saints were also virgins, and the church could not

deny their holiness. This caused a catch 22 situation, where women

were to be loathed and reviled, but also revered and worshiped.

While sex was regarded and somewhat necessary for procreation,

many women chose to live a life of celibacy and religious devotion.

This was often seen by family as a blessing.

Prayers from a nun were believed to be more powerful than prayers

from a lay woman. A dowry was not required for a marriage that

would never happen and it many cases, it was the only way for

a girl to obtain a really good education.

In many instances, the choice for a woman to remain a virgin,

even after marriage was not enthusiastically greeted by the family

or spouse. A woman who remained chaste, although admired for her

purity and devotion to God, was certainly putting her health at

risk by not gaining enough male seed or by the poisonous humours

which were not being released.

Copyright

© Rosalie Gilbert

All text & photographs within this site are the property of

Rosalie Gilbert unless stated.

Art & artifact images remain the property of the owner.

Images and text may not be copied and used without permission.

|