Medieval

Clothing Care

Traditional Remedies & Recipes for Care &

Management of Clothing

CLEANSING - WATERPROOFING - STAIN REMOVAL - RESTORING

COLOUR - RE-HEMMING TO EXTEND WEAR

- IRONING - CARE OF FURS - STORAGE OF CLOTHING

How

did medieval women wash their clothes? Did they wash them? Where?

And with what? It's hard to imagine washing some of those grand

silk velvet court clothing down at the stream. And if one lived

in the city, what then? How

did medieval women wash their clothes? Did they wash them? Where?

And with what? It's hard to imagine washing some of those grand

silk velvet court clothing down at the stream. And if one lived

in the city, what then?

We know that in medieval

London, townswomen washed at a common wash-house. It was a woman's

domain, where news and gossip was exchanged while washing clothing.

In medieval Spain, any bridge leaving town was required to be

wide enough for two women and their water jugs. Since men were

not expected to be at places where woman washed, only other women

were permitted to act at witnesses in disputes if they happened

at the river or stream.

Fortunately, there is some

information of clothing care which has been preserved for posterity.

The best known examples of domestic instruction come from a treatise

known as the Goodman of Paris which was written in 1393

by an elderly Parisian for his 15 year old bride. It is primarily

concerned with good behaviour and on the running of a household.

Here and there, in other manuscripts, a snippet of information

also appears.

Cleansing

of clothes

It is generally accepted that outer clothes were not washed after

every wear, in the same manner that you would not wash an overcoat

or wool jacket after every wear. Heavy outer clothing was shaken

after wear to remove dust, sometimes with a light beating with

a brush or whisk of dry twigs.

General clothing at home could be rinsed carefully by hand in

a tub of heated water. Underclothes were rinsed more frequently

and hung to dry over a pole. Woolen clothes with a long nap could

be reshorn when they were very dirty or worn to expose a fresh

new surface.  The

cost of shearing was averaging 1s a cloth at the time of Bogo

de Clare. It was a skilled procedure which was deemed to be fairly

expensive. The

cost of shearing was averaging 1s a cloth at the time of Bogo

de Clare. It was a skilled procedure which was deemed to be fairly

expensive.

Soapwort, Saponaria officinalis

(at right), was a herb used for cleaning cloth and clothing. Also

known as bruisewort, dog cloves, fuller's herb and latherwort,

soapwort grew originally in northern Europe until its introduction

to England by Franciscan and Dominican monks. When the leaves

are crushed, they make a fine lather like a liquid soap which

works well and is extremely gentle on delicate fabrics.

By the end of the 16th century the use of soapwort had become

widespread in England for laundering, fulling and washing dishes.

Many museums still use soapwort to this day for its ability to

gently cleanse delicate fabrics.

The use of the herb marjoram, Origanum vulgare (also known

as organum or oregany), lent its scent in washing waters.

According to a British historian,

washing at the wash-house was rinsed, twisted and beaten where

the tongues are quite as active as washerwoman's beetles.

Waterproofing

We know from English warderobe records of the 14th century, that

wax was bought specifically for the purpose of waxing garments

for weatherproofing.

Exactly which garments were treated this way is not mentioned

but it can be assumed that they were outer garments for winter

or wet weather, most likely cloaks. This was not an option for

peasants who would have used the wax for more important things,

and would have relied on felted wool for protection from the elements.

Happily, felted wool is remarkably weatherproof.

Stain

removal

There are many interesting medieval recipes for the use of stain

removal on clothing. Fuller's Earth was recommended if soaked

in lye for other kinds of stain removal. It must be applied to

the stain, allowed to let dry and then rubbed.

Ashes soaked in lye and put onto the stain was also believed to

be good.

For dresses of silk, silk damask, satin, camlet 'or other material',

soak and wash the stain in verjuice (from Middle French vertjus

"green juice" - an acidic juice made by pressing unripe

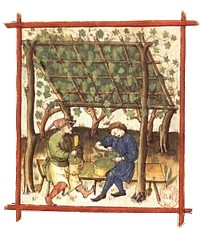

grapes) and it will be cleaned. An image of verjuice being made

from the 14th century French manuscript, Tacuinum Sanitatis,

is shown at right..

Recipes for the removal of

grease and oil were somewhat more complex. One recipe is such:

To remove grease or

oil stains, take urine and heat until warm. Soak the stain

for two days. Without twisting the fabric, squeeze the afflicted

area, then rinse. As an alternative for stubborn greasy or

oily stains, soak in urine with ox gall beaten into it, for

two days and squeeze without twisting before rinsing.

Chicken feathers were also

recommended as a cleaning aid. Firstly they must be soaked in

very hot water then wet again in cold water. The stain may then

be rubbed with the feathers and it will be clean. Exactly how

successful the feathers method was is unclear.

Restoring

colour to faded garments

Remedies to restore the fading were also available. This advice

is offered:

On a pale blue garment,

a damp sponge dipped in clear, clean lye should be squeezed

out and then wiped over the offending area, or to restore fading

on clothes of other colours, use very clean lye with ashes on

the spot. It must be left to dry, then rubbed. The colours shall

then be restored.

If a dress is of silk, silk

damask, satin, camlet 'or other material' soak and wash the stain

in verjuice which has been stored without salt and its colour

will be restored.

Re-hemming

to extend wear

We

know that the parts of a women's gown which wear most are the

cuffs and the hem. Our medieval woman counterparts faced the same

issues as us today, and it comes as no real surprise to see that

their solutions were the same. We

know that the parts of a women's gown which wear most are the

cuffs and the hem. Our medieval woman counterparts faced the same

issues as us today, and it comes as no real surprise to see that

their solutions were the same.

It was not unknown for a woman to cut the very hem of her gown

off when it was too ragged and re-sew it a little shorter or to

replace it with a strip of new fabric.

Shown at right is a picture from the Romance of Alexander showing

a woman catching butterflies who appears to have rehemmed her

dress.

At first I thought that this may be purely decorative, but in

Toni Mount's book, Everyday Life in Medieval London, we

read that in 1320, the household wardrobe accounts of Edward II's

wife Queen Isabella herself had garments re-hemmed to prolong

the wear of them and save the cost of new gowns. This could hardly

have been an unusual thing to do, or it would have been much made

of.

Ironing

Many people consider the iron to be a modern invention but versions

of tools used to flatten and de-crumple clothes have been around

for centuries. Vikings from Scandinavia had early irons made of

glass and roughly mushroom-shaped by about the tenth century.

These were also called linen smoothers. The smoother was warmed

in steam before it was rubbed across the clothing.

According

to historians of domestic household appliances, it was during

the 1300s that the tool we recognise as an iron first appeared

in Europe. According

to historians of domestic household appliances, it was during

the 1300s that the tool we recognise as an iron first appeared

in Europe.

It was comprised of a flat piece of iron with a metal handle attached.

The flatiron was held over or in a fire until it was heated, when

it was picked up by the handle with a padded holder. A thin cloth

was placed between the iron and the garment in order not to dirty

the clothing whilst the ironing process took place.

The iron above is described as having a salamander-shaped handle

and dates to the 15th century.

Care

of furs

Fur was extensively used throughout the medieval period both as

trimming for clothing and as linings. Cleaning furs without damaging

them, especially the hems which came in contact with floors and

mud, was necessary.

A remedy to revive furs or fur skins which have become hard through

wetness was given as: the fur must be removed from the garment

and sprinkled with wine. It should then be

'sprayed by mouth as

a tailor sprays water on the part of a dress he wishes to hem'.

Flour must be put on the

wetted parts. It must then dry for a day or so, before rubbing

well and it will return to its original state.

Storage

of clothing Storage

of clothing

Wardrobes as we know them today do not seem to be depicted with

great regularity in medieval art and it is thought that general

storage of linen and clothes was in large wooden chests.

Pictured right is a detail from the 1470 painting, The Birth

Of Mary showing a large, wooden chest for the storage of linen.

A

15th century German manuscript, at left, shows a garment hanging

on an early version of a coathanger, but this was for the sewing

of the garment, and not for storage. A

15th century German manuscript, at left, shows a garment hanging

on an early version of a coathanger, but this was for the sewing

of the garment, and not for storage.

My own thoughts are that many of the garments were heavy wools,

often lined with furs, and storage on a coathanger may have produced

extra strain of the shoulder seams. Chests of drawers do not seems

to have been used. Chests themselves, though, are shown in many

artworks.

Airing of dresses was encouraged

to avoid moths and their larvae. This was a practice which must

be done on a sunny day in the summer and dry months for if the

dresses are put away in a chest after airing on a cloudy day,

the cold air will be folded into the dress and encourage vermin.

Roses of Provins were also

considered the best for putting in dresses. The Goodman of

Paris says that these must be dried in mid-August and sifted

in a seive so that all the worms fall out and then the petals

may be scattered on the dresses.

Pest-repellants Pest-repellants

Many household washing and storing of cloth and clothing involved

the use of herbs either to make the linen sweet-smelling or to

discourage harmful insects.

In the late 15th century, a mixture of powdered anise and orris

iris florentina was used to perfume household linen in

storage. Medieval linens were also scented with lavender, Lavendula

vera, by being stored with it or rinsed in lavender water.

Rue, Ruta graveolens,

also known as the Herb o' grace o' Sundays was used in linens

to keep away bugs and noxious odors. The image at right from the

Tacuinum Sanitatis shows two men collecting rue.

Wormwood, Artemesia absynthum,

was the most common element cited in recipes to protect medieval

clothing from damage whilst in storage. It was often placed among

woolen cloths to prevent and destroy moths.

A mixture of wormwood, southernwood, the leaves of a cedar tree

and valerian mixed together and put wherever clothes were stored

was thought to help repel moths and other vermin.

Copyright

© Rosalie Gilbert

All text & photographs within this site are the property of

Rosalie Gilbert unless stated.

Art & artifact images remain the property of the owner.

Images and text may not be copied and used without permission.

|