|

fabrics

& sewing

sewing

tools

sewing

techniques

basic

medieval

clothing

sewing

tutorials

commercial

patterns &

what to do

about them

dyes

&

colours

fabric,

fur

& leather

names

embellishments

& embroidery

buttons

& lacings

|

Medieval

Sewing Tools

NEEDLES - PINS - THIMBLES - SCISSORS & SHEARS

- NEEDLECASES - REELS - IRONS

LUCETS - SPINDLES - SPINNING WHEELS - LOOMS

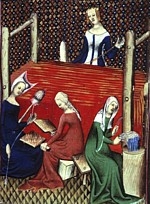

Sewing is an occupation which is usually the domain of women.

During the medieval period, guilds stipulated what women could

and could not produce commercially. On a domestic level, women

at home produced everything but professionally, some industries

were dominated by men.

The tools for basic sewing

have not changed over thousands of years. The shapes of some of

them- like scissors- have varied slightly, but pins and needles

and the way women use them, have not.

Sewing tools include: needles, pins, scissors, snips, shears,

thimbles, needlecases, pin cases, reels, awls, and lucets. All

of these items may be found in the modern woman's sewing basket.

The detail at right is from a 15th century illumination The

Holy Family and shows Mary with a basket of sewing tools.

The most comprehensive listing of sewing tools comes from Hugh

of St Victor when he talks about the tools required for textile

arts. Although he lived between 1096 and 1141, he cites:

Textile manufacture

includes all types of weaving, sewing, and spinning which

are done by hand, needle, spindle, awl, reel, comb, loom,

crisper, iron or any other kind of instrument out of any kind

of material of flax or wool, or any sort of skin, whether

scraped or hairy, also out of hemp or cork, or rushes or tufts

or anything of the kind which can be used for making clothes,

coverings, drapery, blankets, saddles, carpets, curtains,

napkins, felts, strings, nets, ropes; out of straw, too, from

which men usually make their hats and their baskets. All these

studies pertain to textile manufacture.

Sewing

needles

One of the most basic and long-lived of all the sewing tools is

the needle. Along with pins, needles have been used for garment

making since time immemorial.

In 1370, we find references to needle-making for sewing from Germany.

Prior to that, there are records of bookbinders and shoemakers

needles made from hog bristles.

Needles could be made from bronze, iron and bone, which was readily

available to poorer women. The needle at right is made of bronze

and dates between the 14th and 15 centuries. It was found at Threave

Castle, in Scotland.

Pins Pins

Pins have been used for sewing and also as a dress accessory,

so many finds from archaeological digs have decorative ends with

glass beads.

It is likely that plain pins with smaller non-decorative heads

were used for pinning fabric together prior to sewing in the manner

which we do today.

Shown at left is a collection of brass, coil-headed pins found

at th foreshore in front of one of Henry VIII's palaces in Greenwich,

England.Tudor. They are dated to the 16th century.

Thimbles Thimbles

Thimbles have also been used for centuries.

The dimples in the surface allowed the thimble to protect the

finger while pushing a needle through fabric or leather. A thimble

is generally made out of strong leather or metal, although some

older manufacturers used horn and ivory.

The large thimble to the left is an example of a brass, domed

thimble from my own collection. It has hand drilled holes and

dates to the 14th-15th century. The second thimble shown at the

right is also from London, England from the 14th century, also

both constructed from brass and has a small hole at the top which

may or may not have been acquired in the manufacturing process.

The

silver thimble at the right is also from London, England and is

hand-punched. It is silver-gilt and bears an inscribed motto in

medieval French, "MA JO IE" which means my joy.

It also has engraved leaves. The

silver thimble at the right is also from London, England and is

hand-punched. It is silver-gilt and bears an inscribed motto in

medieval French, "MA JO IE" which means my joy.

It also has engraved leaves.  Such

in item would have been quite expensive and used for fine work

by a wealthy woman. Such

in item would have been quite expensive and used for fine work

by a wealthy woman.

The thimble at left is known

as a ring thimble because its design and open top lets

it be worn on the finger like a ring. It is made of brass and

dated to the 15th century England.

It comes from The

Gilbert Collection.

Scissors

and shears

Another of the basic sewing tools which has survived almost unchanged

is scissors. Scissors proper and sprung shears have both been

found throughout the medieval period and although of varying design,

are much like the ones we have today . .

The scissors shown at right

are from the medieval period but the exact names and references

I have are in Russian so you may look at the pictures until I

find an English language translation, but I believe they are either

from the London finds or the Novrogod finds.

The one at left of the pair are from the same find and are almost

identical to the ones found in viking excavations and to the ones

we use today. They are commonly depicted in illuminations where

sheep shearing or the cutting of large bolts of cloth are shown.

The

scissors shown below right date between 1350 and 1400. They are

made of iron and were found at Baynards Castle in England. They

are also very similar to scissors which have been produced in

the 20th century. The

scissors shown below right date between 1350 and 1400. They are

made of iron and were found at Baynards Castle in England. They

are also very similar to scissors which have been produced in

the 20th century.

Needlecases

and pincases Needlecases

and pincases

What to keep one's small sewing tools in to save them getting

lost has long been a question faced by women from as long as they

had tools to use.

Needlecases and pincases during the medieval period were usually

more or less cylindrical with a top which lifted off but remained

attached via two cords, one at each side.

Many of these were made of metal and could be quite ornate although

there have been a few examples of worked leather as well.

The 13th century hexagonal

needlecase shown at near left is made from silver and has an ornate

pattern embossed into its sides. It would have belonged to a wealthy

woman. The needlecase shown at far left is dated from the 16th

century in Venice but it is typical of the style used in the preceeding

centuries.

Bobbins,

reels and threadholders Bobbins,

reels and threadholders

Threadholders, bobbins and reels are another sewing item which

has barely changed shape over the centuries. The two most popular

shapes are long and thin, or shorter with a wide top and foot,

similar to the ones of our grandmothers era with or without the

hole at the top and bottom.

At the left is an example

of an existant wooden thread holder from London.

Irons

Most modern households have an iron but only the well-off medieval

woman might have an iron. Laundry accounts seem to mention some

specific services- darning and washing, but not others. It seems

that irons were used during the medieval period to flatten household

linens and clothing.

Some were made of ceramic, some of Italian soapstone and others

forged from iron by blacksmiths. In Textiles and Clothing

published by the Museum of London, it mentions linen smoothers

made from glass as being also known from the medieval period.

Among the comprehensive listing of sewing tools by Hugh of St

Victor who lived between1096-1141, is listed-

loom,

crisper, iron or any other kind of instrument out of any kind

of material... All ... pertain to textile manufacture. loom,

crisper, iron or any other kind of instrument out of any kind

of material... All ... pertain to textile manufacture.

The image at left is of a

15th century iron described as with a salamander shaped-handle

made from iron. It comes from the Allemoli Collection of

antique irons and is used here without permission. If it is your

iron, please contact me so I may seek your permission or have

the image removed.

Lucets

The

lucet is a cord or lace-making tool which has been used since

Saxon times. By wrapping the thread around the prongs in a manner

similar to French knitting, a square braid or lace is produced. The

lucet is a cord or lace-making tool which has been used since

Saxon times. By wrapping the thread around the prongs in a manner

similar to French knitting, a square braid or lace is produced.

This lace is strong, durable and doesn't easily slip when used

for garment fastenings. As far as I can tell, there are no illustrations

of braid being made using a lucet (or lucette, in French) but

braid found matches that which could be made with a two-pronged

tool such as these shown here.

Shown at near left is an

item believed to be a bone lucet from York, in England. The decorated

item at the right is made from whale bone and generally believed

to be a lucet from prior to the 12th century.

Spindles

and spindle whorls Spindles

and spindle whorls

The

spindle and drop spindle, had long been in use before the medieval

period, and its use continued right throughout the early and middle

ages, only dwindling in use towards the very end of the 15th century. The

spindle and drop spindle, had long been in use before the medieval

period, and its use continued right throughout the early and middle

ages, only dwindling in use towards the very end of the 15th century.

Even with the introduction

of the spinning wheel, the spindle was not abandoned straight

away. It was cheaper, portable, available for home production,

portable and surprisingly, still produced an end product which

was superior in quality to that of the thread spun on the wheel.

A

spindle was essentially nothing more than a slender, shaped stick

with a weight at the bottom called a whorl. The wool, already

cleaned and combed on the distaff was pried from the distaff onto

the spindle while it was manually spun. This produced a fine thread

which could then be woven into cloth. A

spindle was essentially nothing more than a slender, shaped stick

with a weight at the bottom called a whorl. The wool, already

cleaned and combed on the distaff was pried from the distaff onto

the spindle while it was manually spun. This produced a fine thread

which could then be woven into cloth.

The wooden distaff head shown at right is dated to the 15th century,

and was used for linen. It is 115mm tall and was found in Dordrecht.

The spindle whorl pictured at left comes from England and is made

from the bone of a cow's leg.

The image detail at left

is from the Luttrel Psalter, from the 14th century, and

shows a women with her spindle and distaff outside feeding the

chickens.

Spinning

Wheels

The late 13th century saw the introduction of the spinning wheel

into cloth production. The earliest illustration of a spinning

wheel in use is dated at 1237 from Baghdad.

Originally,

the spinning wheel was set on a table and powered by hand, as

shown in the detail image from the 14th century manuscript, the

Luttrel Psalter. The image shows that the table is mounted

on wheels at one end, presumably to allow for the wheel to be

moved. Originally,

the spinning wheel was set on a table and powered by hand, as

shown in the detail image from the 14th century manuscript, the

Luttrel Psalter. The image shows that the table is mounted

on wheels at one end, presumably to allow for the wheel to be

moved.

At first, spinning wheels were not very well received because

the thread was rough and uneven and much better results were gained

spinning by hand. In 1280, it is recorded that the Draper's Guild

banned its use for this very reason.

Eventually, the spinning wheel produced better results, but according

the the 14th century Florentine book, Arte della Lana,

it was recommended that the shorter fibres of wool be saved for

use on the spinning wheel to make thread for the weft of a cloth,

and the longest fibres only used for hand spinning to make the

warp, which was where the fabric gained its strength.

During the 15th century, the foot pedal was added, leaving both

hands free to focus on the wool.

Looms

While a women was in charge of producing yarn for weaving on the

spindle or spinning wheel, the actual weaver of the household

was was usually the head male.

There were two styles of loom during the medieval period. The

early looms were upright, the later ones were horizontal. Upright

looms are still in use today for the manufacture of handmade tapestries.

Pictured at left is a detail manuscript by Boccaccio de Claris

Mulieribus showing a woman working at an upright loom.

By

the 12th century, the horizontal loom had been mechanized and

was operated by foot-treadles. Instead of weaving the heddle bar

by hand, the weaver needed only to push the treadles and every

second warp thread rose above the others. By

the 12th century, the horizontal loom had been mechanized and

was operated by foot-treadles. Instead of weaving the heddle bar

by hand, the weaver needed only to push the treadles and every

second warp thread rose above the others.

The next push of the treadle lowered those and raised the next

set. The warp threads were rolled around a cylinder of wood at

the far end of the loom and unrolled as needed. The finished cloth

was gathered at the front of the loom.

By the 15th century, men's

domination over the weaving industry had waned and women were

also more regularly employed as weavers.

At the right is a detail from a 15th century image of Boccaccio's

de Claris Mulieribus. It shows the horizontal loom along

with the other steps necessary to produce the thread prior to

weaving- carding, spinning and cleaning.

Copyright

© Rosalie Gilbert

All text & photographs within this site are the property of

Rosalie Gilbert unless stated.

Art & artifact images remain the property of the owner.

Images and text may not be copied and used without permission.

|