Medieval

Women's Underpants

EXISTING GARMENTS - SOURCES - UNDERPANTS IN HOUSEHOLD

ROLLS - THE TOPSY-TURVY WORLD

UNDERGARMENTS & HORSE-RIDING

A

Question of Underpants, Trewes, Clouts or Braes A

Question of Underpants, Trewes, Clouts or Braes

It seems to be generally accepted as "one of those things

that everybody knows" is that medieval women did not wear

underpants.

I believe this is not so.

To women of child-bearing ages, this would certainly not be an

appealing thought, especially when considering certain times of

the month.

To date, I have only seen

a couple of clear images of a woman wearing underpants in art,

one shown at right and the other below. There are a couple of

written references to underpants for women, but not many. This

does not mean that they never wore them.

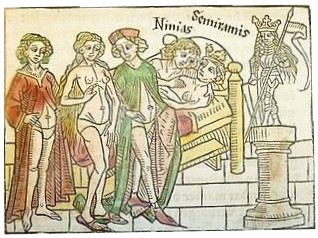

The image at right shows Semiramus who was a mythological queen

of Assyria, in a woodcut from Boccaccios Famous Women dated

1474, now in the Bavarian State Library. While it does show figures

from a legend and not actual, living people, I personally feel

that these underpants were not painted on for modesty.

Sources

for medieval women's underpants

Underpants for medieval women aren't recorded or written about

greatly, although Ian Mortimer's book, A Time Traveler's Guide

to the 14th Century mentions aristocratic women's clouts as

a form of linen braes for women to wear when nature forces her

to do so.

In household rolls and in warderobe records they are not listed

specifically, except in one instance which is within the ordinances

issued to tailors concerning the value of the clothing which could

be charged for a particular garment.

In the book Fashion in

the Age of the Black Prince, Stella Mary Newton asserts that

a French Tailor's ordinance in 1350, the Ordonnances des rois

de France, mentions the cost of a chemise as no more than

8 deniers and for the robbes-linges (which were presumably

linen underpants)

the price was to be

the usual one for masculine underants of the same style.

This certainly seems to indicate

that women may have worn underpants of a similar style to men.

Astrida Schaeffer is a historian

who has investigated medieval women's underpants. Her independent

research has uncovered two pieces of further evidence for underpants

being worn seperate to the use of them for the menstrual cycle.

I quote her here in full, as her observations are quite compelling.

She writes first about a

tale involving fiction characters, and then further on an actual

legal case where underpants are a crucial part of evidence in

the trail.

"In the Roman de

Renart, it is clear that female braies were understood as a

mark of modesty - which of course implies that they were worn

by women. Called to account for his assault on Dame Hersent,

Renart insists the act was consenual because "he did not

remove her braies" ("et puis qu'i n'i ot braies traites")

(Le Roman de Renart, Branch I, 1287, cited in Burns, note 23).

In other words, since Renart did not have to remove Dame Hersent's

braies, she must have done so, signaling her sexual availability

and therefore his innocence. The presence or absence of the

braies is central to the argument."

The trial in which underpants

worn by females is mentioned can be found in Ravishing Maidens:

Writing Rape in Medieval French Literature and Law by Katheryn

Gravdal. Astrida Schaeffer again shares what she has discovered

about this court case in the early 14th century.

"...the young apprentice

Perrette la Souplice, a very real person living in Paris in

1337, is on official record as wearing her braies, which proved

to be a crucial piece of evidence at an actual, not literary,

trial. Perrette de Lusarche and Perrette la Souplice, both aged

twelve, were assaulted by Jehanin Agnes and their case went

to trial. The trial transcript includes the following account:

"Là, en un selier, fist entrer, oultre son gré

et par force, ladicte Perrete la Souplice, et la jeta à

terre, et avala ses braies, et se mist sus lui..." (There

in a cellar he made her go, against her will and by force, the

said Perrette la Souplice, and he threw her to the ground, and

pulled down her braies, and got on top of her...)

This shows that in 1337,

when the case was taken to court, underpants were worn by these

girls. It is a rare glimpse into the private world of feminine

undergarments which we would not have otherwise heard of.

Existing

garments

Until 2008, no existing underpants. In July 2008 investigations

for re-construction were carried out at the Castle Lengberg in

Nikolsdorf, East Tyrol, Austria. A vaulted spandrel was discovered

in the south wing which was filled with backfill- possibly to

level the floor when a further level was added. The fill was stored

for subsequent sorting at a later date.

When examined, it was revealed that the fill consisted of layers

of dry material, among them organic material- twigs and straw,

but also worked wood, leather (mainly shoes) and textiles. Photo

below at right ©Institute of Archaeologies, University of

Innsbruck.

Among

the finds were a pair of linen underpants, shown at right, identical

to those shown being worn by men in illustrations in many artworks. Among

the finds were a pair of linen underpants, shown at right, identical

to those shown being worn by men in illustrations in many artworks.

Beatrix Nutz was part of the archaeological team who investigated

the textile fragments, and wrote of her findings supporting the

dating of the underpants to approximately 1480:

On the contrary –

a closer examination of the pieces in question showed that no

textile techniques were used in their construction that would

not fit to the time period. All applied techniques were common

during the 15th century and none of them developed later. Besides

- all other textiles from this find, like fragments of dresses,

shirts, trousers, laces etc., fit well to the 15th century.

The question of whether the

underpants found were worn by a man or a woman is not 100% conclusive

but due to the fragments of hose found with them, Beatrix Nutz,

the archaeologist who has studied them, believes that they were

worn by a man.

It is interesting to note that the underpants were found along

with items of breast support which we would call bras and corsolettes

today. Although probably worn by a man, they give a great insight

into what may have been available to the medieval woman at that

time.

Underpants

in household rolls

Perhaps there is no mention of women's underwear in household

accounts because most of the records and rolls were written by

male stewards who did not bother with such trifling and unimportant

items. Perhaps the items were of very little value and were not

recorded for this reason. Perhaps it was not an area any man wished

to enquire about.

It was then, as it was during the following centuries, private

and "unmentionable".

It

is also possible that ladies' underpants do not rate a mention

because they were actually not worn at all and that in images

underwear was painted in for modesty's sake. It

is also possible that ladies' underpants do not rate a mention

because they were actually not worn at all and that in images

underwear was painted in for modesty's sake.

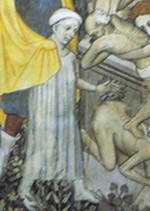

It does not seem that extra

modesty was required in the fresco The Fountain of Youth

painted from 1411 to 1416 by di Manta where the woman in question

was already covered by a fine chemise. A closer examination shows

a horizontal line and whitening where her underpants seem to be

although no corresponding whiteness at her breasts. In a time

period when sunbaking and tan lines were not known, it seems unlikely

that the white patch is merely her white bottom. Detail shown

at left.

Most other images show women bathing without pants or with their

privvy parts modestly covered by their hands or hair.

As a woman, I find this insistence

at the lack of underpants to be a little perplexing. What of the

menses? It is certain that women menstruated and it follows that

some method of dealing with the same was employed.

Many times I have been asked, usually in hushed tones and in a

private place, about underwear at this time of the month. Although

I have repeatedly read that women wore nothing, I believe that

in this day and age, if women feel the necessity to speak privately

on this matter, they would probably have been less inclined to

discuss it with any kind of record-keeper in the middle ages.

I feel some kind of underpants must have been worn, at least during

some times of the month.

Interpreting

underpants in art Interpreting

underpants in art

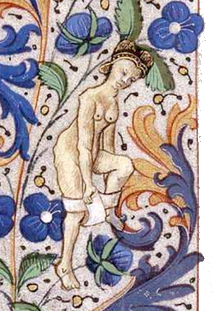

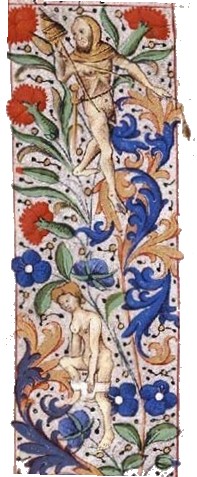

Although there are only a few images of women wearing underpants

in medieval art, care must be taken in understanding these in

their full context.

A single image alone might show a women wearing underpants, but

other images on the same page show that the text indicated a world-gone-crazy,

topsy-turvy situation where the men are shown doing women's work

and the women are wearing the pants as a metaphor for running

the household.

Shown at right is a section of a marginal illumination which shows

exactly this. We see the wife putting on the pants, and the husband,

although still wearing his very masculine sword, using a distaff

which is usually a key icon of women's work.

Both of the images here are from the Biblioteca Nacional de Espana's

Horas de Alonso Fernández de Córdoba. It

is dated around 1465.

While these do show women

in underpants, context is the key.

Undergarments

and horse-riding

It is also known that many women rode horses although usually

on a saddle with a kind of foot platform which permitted genteel,

well-bred women to ride sidesaddle.

The Histoire de Guillaume le Mareschal, written circa 1226 tells

us:

While fleeing enemies,

Empress Matilda was riding cumme femme fait, en seant

as ‘women do, sidesaddle.’ Her Marshal told

her she would have to part her legs and ride astride because

they needed to get a move on. ‘Les jambes vos covient

desjoindre e metre par en son 'l’arcum.’

This shows us that although

a woman might choose to ride with her legs at the side, it was

not unknown for a woman to ride astride when required. Medieval

art, too, often confirms this with images like the detail from

the 14th century RomanceofAlexander, folio 80v which shows women

out hawking and riding astride.

Some

other medieval women, like Margaret Paston, regularly rode in

her travels and according to Frances and Joseph Gies book, Women

of the Middle Ages, she probably rode astride as women

had always done rather than side saddle which was just coming

into vogue in the early 15th century. Some

other medieval women, like Margaret Paston, regularly rode in

her travels and according to Frances and Joseph Gies book, Women

of the Middle Ages, she probably rode astride as women

had always done rather than side saddle which was just coming

into vogue in the early 15th century.

As any horsewoman would be

well-aware, to ride astride vigorously with no underwear for protection

would be unlikely for all but the shortest periods. It is possible

that for short journeys where the rider does little more than

walk, protection other than the voluminous folds of gown were

sufficient for a woman's delicate nether regions. For extended

journeys, protection might have been warrented.

In Mistress, Maids and

Men by Margaret Labarge, we learn that the Countess of Leicester

seemed to have an undergarment made of fine leather. The skins

were delivered to her tailor, Hique, who also purchased 3 ells

of canvas for the same purpose. The Latin word used in the original

household roll is cruralia which suggests some kind of

shin coverings. It is known that the Countess rode astride often

and it is suggested by Margaret that these items were used to

make some kind of riding-breeches to protect her legs and underneath.

Copyright

© Rosalie Gilbert

All text & photographs within this site are the property of

Rosalie Gilbert unless stated.

Art & artifact images remain the property of the owner.

Images and text may not be copied and used without permission.

|