|

Employment

- A Medieval Woman's Work

PEASANTS - TOWNSWOMEN - NOBLEWOMEN - OTHER WOMEN

It

would be impossible to provide a comprehensive overview of women's

employment opportunities during the medieval period in full. I

have included a brief look at what women generally had the opportunity

to do, each according to her social status. It

would be impossible to provide a comprehensive overview of women's

employment opportunities during the medieval period in full. I

have included a brief look at what women generally had the opportunity

to do, each according to her social status.

This is by no means definite in every single case and there are

many records of women who worked outside the normal conventions

in occupations usually reserved for men alone.

Women are almost never shown

in paintings or manuscripts waiting on tables, a job far too important

to be entrusted to mere women. Serving food at a feast or to an

honored guest was highly esteemed and therefore a job which belonged

to the head Steward of a house- a man. In a poorer household,

of course, the women of the house would have brought food to the

table for her husband and family.

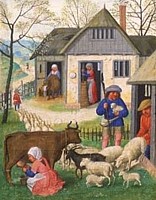

Shown at top right is a detail

from the month of April from the da Costa Book of Hours

illustrated in 1515 by Bening. It shows a domestic scene where

men and women work together at a variety of menial jobs- milking

the cows, tending the sheep and churning butter.

Peasant

and rural women Peasant

and rural women

Peasant women were usually employed in menial work outside the

home as well as raising their own family, taking care of their

own vegetable patch and any poultry they may have had. Shown below

is scene from the Tacuinum Sanatatis showing women working

with men in a rural setting.

Young, single English peasant

women rarely had the capital to go into business for themselves

brewing or baking. They were often employed as live-in servants

although recent studies have shown that it was a very poor peasant

who could not afford help of her own.

Girls might have worked for a neighbour, relative or be engaged

in household work in the nearest town. Working as a servant was

not seen as a demeaning work choice and occasionally in household

rolls, children are described as being servants of their own parents.

With only the very poorest peasant women unable to afford some

domestic help, there was usually no class difference between mistress

and maid.

A woman's status came from her being a wife, rather than where

she was employed.

Once married, it was usual

for a women to give up her service to someone else and be mistress

of her own home. Rural women were also engaged in spinning and

preparation of fibres for spinning and weaving- scouring flax,

combing wool and hemp and assisting with sheep shearing.

There was very little that

a peasant woman might not be called to do and many illuminations

show women working in the fields alongside men.  They

were hired to do various types of agricultural labour, including

planting peas and beans, weeding, reaping, binding, thatching,

haymaking, hay stacking, threshing and winnowing. They

were hired to do various types of agricultural labour, including

planting peas and beans, weeding, reaping, binding, thatching,

haymaking, hay stacking, threshing and winnowing.

Of the two work options,

live-in servitude was a more secure place of employment and the

wages were slightly higher than seasonal work. Outdoor work was

usually, but not in all cases, paid at a rate slightly less than

men, although women thatchers and reapers were often paid at the

same rate as their male coworkers.

The Statute of Cambridge in 1388 shows that the maximum

wage for women laborers and dairymaids was 6 shillings per year,

much less than the top wage of 10 shillings.

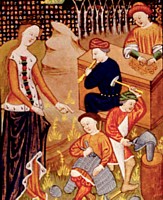

Shown at right is a detail from a border decoration from the Romance

of Alexander dated between 1338 and 1344. It depicts a peasant

woman working in the fields and using the same equipment that

a men would also have used. The picture is slightly unusual in

that the woman is wearing a short dress and her legs are visible.

Townswomen,

urban & middle class women Townswomen,

urban & middle class women

Women who lived in towns, were middle class or were engaged in

some kind of merchant activity were better off than their counterparts

in the country, although it it not to be thought that the hours

they worked were any less. As well as a full time job, townswomen

also had a family to care for and a small household to run and

probably one or two staff of her own to manage.

Many townswomen were women who had previously lived in the country

and had moved a nearby town seeking full-time employment. This

was not seen as a lifetime occupation, but rather an employment

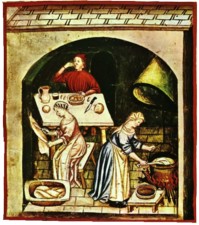

option suitable for single women until marriage. Shown at left

is a detail from the Tacuinum Sanitatus showing middle

class women working in the home.

Many

women were shopkeepers and wage earners. A women whose husband

had died, may have continued his trade alone as a femme solo,

and be authorised to hire apprentices to carry on her husband's

work. Some women were permitted into Guilds but in many cases

they were not admitted solely because of their gender and not

because of lack of skill or experience. Very few women were formally

apprenticed, although many were trained in trades informally.

Wives and daughters of skilled tradesmen often fell into this

category. Many

women were shopkeepers and wage earners. A women whose husband

had died, may have continued his trade alone as a femme solo,

and be authorised to hire apprentices to carry on her husband's

work. Some women were permitted into Guilds but in many cases

they were not admitted solely because of their gender and not

because of lack of skill or experience. Very few women were formally

apprenticed, although many were trained in trades informally.

Wives and daughters of skilled tradesmen often fell into this

category.

Records of women who worked

in towns include, but are not limited to, the following occupations:

hat-making, cobbling, glover-making, girdle-making, haberdashery,

embroidering, purse-making, cap knitting, spinning and silk weaving.

They were involved in the food industry in the areas of brewing

of ale, butchery, innkeeping, selling garlic, fresh bread, flour,

salt, candles, butter, cheese, fish and poultry.

While many of the textile arts were dominated by men, embroidery

seems to have a larger percentage of women workers than other

guilds. Records from the very end of the 13th century show that

of the 94 registered embroiderers in Paris, 79 were women.

It may come as a surprise

to some that women were also employed as chandeliers, iron mongers,

smiths, goldsmiths, skinners, bookbinders, painters, spicers and

farriers. Possibly these were widows who were able to carry on

their husband's trade. Shown at right is a woman blacksmith or

farrier at work from the Holstein Bible from the 1330s.

Noble

and upper class women

There are many misconceptions attached to the noble woman, and

how she spent her days. In reality, a woman in the upper classes

might not be called upon to do hard, manual labor, but she was

in no way exempt from a busy, managerial role.

An

upper class woman was almost always a land owner, inherited as

part of her dowry at marriage. As well as her own holdings, a

wife had to be able to replace her husband during his absences.

Considering the number of wars and crusades which occurred during

the medieval period, these absences could be frequent and lengthy. An

upper class woman was almost always a land owner, inherited as

part of her dowry at marriage. As well as her own holdings, a

wife had to be able to replace her husband during his absences.

Considering the number of wars and crusades which occurred during

the medieval period, these absences could be frequent and lengthy.

The lady of the manor oversaw production of the home farm and

dairy. She had to be able to govern the house and hire or fire

the staff who worked under her and know enough about the work

being done to recognise if it was being done well, even if she

was not actually doing the work personally. She also needed to

know how to hire seasonal staff and repairmen and pay them fairly.

Records indicate that a noble woman could, and did, draw up wills,

sue and be sued and make contracts.

Even in a large manor, several

small rooms or cottages accommodated the production of consumable

goods for the estate or the immediate household, its staff and

its guests; all of which required overseeing. A noble lady also

needed good accounting and reckoning skills and was often literate.

The detail at left shows an illumination from a 15th century manuscript

by Boccaccio known as the de Claris Mulieribus showing

Minerva in a supervisory role instructing the making of armour.

Other

Women

Other

occupations provided important livelihoods for medieval women,

and these included a life of religious devotion, healthcare, musician

or prostitution. Other

occupations provided important livelihoods for medieval women,

and these included a life of religious devotion, healthcare, musician

or prostitution.

Women who wished to avoid

marriage or were widowed and wished to avoid further marriages

had the opportunity to take a life of religious contemplation.

This came in many forms, but almost all involved life in a community

under the care of an Abbess.

Beguines were religious women who lived simple lives and were

known for their charitable works. Many of these women were from

the middle or upper classes. Shown at right is a scene from the

right of the Adelheere Altarpiece from 1443.

Other opportunities for women

were to train as healers or midwives. Doctors were needed in towns

of every size and it seems that midwifery was almost an exclusively

female domain. Nurses might have attend the new mother and cared

for the newborn, or worked in a hospital or hospice caring for

the sick, diseased or pilgrims who were en route to a shrine and

had fallen unwell along the way.

Occasionally

we hear of an exceptional woman who took a profession uncommon

to most other women. One such famous medieval woman was Christine

de Pisan who, as a widowed mother of three, and only aged 25,

became a successful writer to support herself and her family. Occasionally

we hear of an exceptional woman who took a profession uncommon

to most other women. One such famous medieval woman was Christine

de Pisan who, as a widowed mother of three, and only aged 25,

became a successful writer to support herself and her family.

Although women did write, it was not a usual career path for most

women. The illumination detail at left shows Christine Presenting

Her Manuscript To King Charles VI of France. It is dated at

1410-1411.

Women who were outside of

the normal roles for medieval women might also be employed as

musicians- jongleuresses and menestrelles. They

usually traveled as part a of small groups of entertainers and

were often the wives or daughters to their male counterparts.

In a few cases, there are records of women in independent roles.

In 1321 in Paris, women were given permission to participate in

the Guild of Minstrels.

Prostitution, as much as

it was frowned upon, was deemed a rather necessary part of life,

and poor women sometimes turned to this in order to make a living.

Towns and cities tried to regulate the clothing a prostitute could

wear and sumptuary laws tried to curtail extravagant clothes which

the lifestyle of a working woman could afford.

Copyright

© Rosalie Gilbert

All text & photographs within this site are the property of

Rosalie Gilbert unless stated.

Art & artifact images remain the property of the owner.

Images and text may not be copied and used without permission.

|